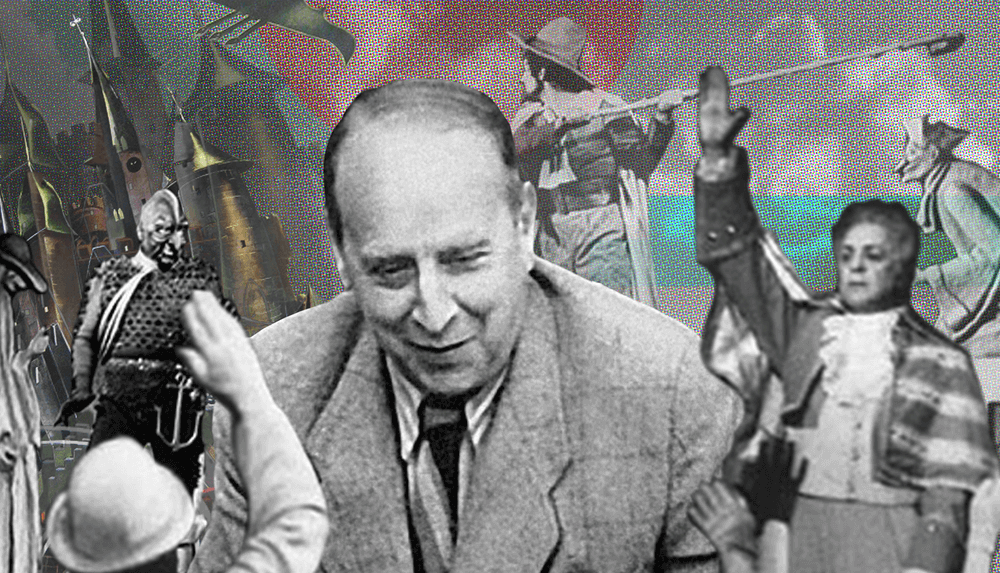

Themes in Eugene Schwartz’s DRAGON

Eugene Schwartz first spoke of his idea for a fairy-tale play about a dragon, whose people are so obedient and controllable, because he maimed their souls, in 1939. The main theme voiced at the time was the criticism of the Nazi regime, however, the feedback he received wasn’t positive due to Russia’s alliance with Germany at the time, so the story was shelved for a few years. Next time he returned to it in 1943, two years after Hitler violated his agreement with Stalin and opened the second front. At the time Schwartz was evacuated from Leningrad to south of Russia, where he began writing Dragon again, and completed it by 1944. The most prominent and obvious theme then was tyranny and its structure.

In the story, Dragon is portrayed as a human for most scenes, because he likes to visit his people “as a friend”. However, he changes heads, and at one time he appears as a retired soldier, deaf in one ear, another time – a tall bourgeois-looking man gentleman, and yet another time he turns into a short angry old man. He misleads his opponent, making him think he’s harmless, friendly, yet he will easily turn monstrous, if he is not obeyed. His power is absolute and there is no hope of winning a fight against him. In the story, it is described that in the first 200 years of Dragon’s reign people tried opposing him, however, he would always destroy the armies and punish anyone close to those who dared fight him, and so people gave up, and the next 200 years they worked hard to adapt. With such a premise, it was no wonder the Censorship Committee of the USSR didn’t see Nazis as the exclusive tyrannical group criticised.

Another theme in the story is, of course, the people themselves. Traditionally in Western mythology the people suffer greatly under a dragon, and when a hero arrives, they beg him to save them and to slay the dragon. However, not here. Schwartz seemed to go more in the direction of the Biblical heroes like Moses and Jesus, whose great deeds to mankind were often quite unappreciated by those they wished to save. Dragon’s people are Pilate’s people, they are afraid of the immediate turmoil, the breaking away of the order of life they’re used to. Like Hebrews in Exodus they fear also the greater retribution of their tyrant for voicing discontent. As a result, everything in those people’s lives is crooked and reversed. The wish to save one’s daughter is considered selfish, while killing the one wanting to save them – heroic, speaking the truth brings dire consequences, and some have forgotten what it even feels like to not utter a lie, carefully designed to manipulate others in some way, and everyone is afraid to be reported to the dragon for some careless word or action. In the end, people become Dragon’s agents of their own censorship. In the end they are complicit in their own enslavement.

In a world where everyone is paralised by fear and spite, there is nothing to want for the soul, and so, another theme emerges in the story: materialism. Dragon’s characters while different from each other, all crave the same things: financing for their project, getting their boss sacked (or executed), so they can take his job, getting the best clothes, the best things. And to earn all that they only have to be the most helpful to Dragon.

The darkest theme, however, is probably the theme of the third act of the story. The dragon is slain, but is he really gone? The power vacuum is quickly filled, and the question arises: was there any hope in destroying tyranny at all?

Rather dark, don’t you think? However, the themes of the dragon aren’t the only ones, there is hope in the story, and in order to find it, we invite you to book your tickets and come and see our show.